Keith Gavin made several requests regarding his final moments, all reflecting his Islamic faith. However, the prison largely ignored these requests, continuing a pattern of insufficient accommodation for the religious needs of Muslim prisoners.

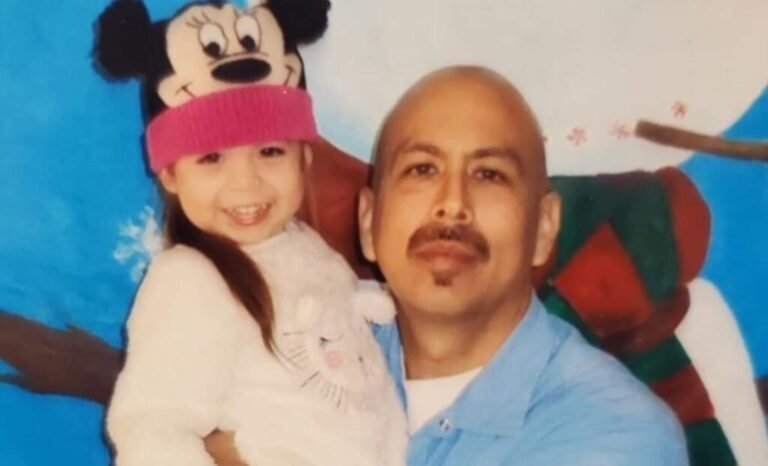

For the past 25 years, Keith Gavin practiced Islam on death row at Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore, Alabama. He served as the imam for the Sunni Muslim inmates during this time and had adopted the Islamic name Kamar Kernell Gavin Gabuniquee, which means “strong prince, strong one, and wonder.” Islam played a significant role in his life, Gavin shared during our conversation in the prison’s visitation room. At 64, he wore a white kufi and had prayer beads draped over his khaki prison uniform.

At 10 a.m. on the day of his scheduled execution, Gavin was facing lethal injection later that evening. He had filed a handwritten appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court the previous day, hoping for a stay of execution. Given the court’s historical reluctance to intervene in death penalty cases, his chances of a reprieve were slim, although the Court had recently halted an execution in Texas at the last moment.

We also discussed a pressing issue: Gavin’s final meal. Warden Terry Raybon had the authority to approve or deny meal requests. Gavin had requested halal lamb, in line with his Islamic dietary laws. However, Raybon had refused to allow the meal, indicating that no change in decision was likely. Gavin’s hope for a stay of execution seemed more promising than his chance of receiving the halal lamb.

This disagreement was part of a broader pattern of conflicts between Gavin and the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) over his final wishes, many of which were related to his Islamic faith. Last month, Gavin had filed a lawsuit against the state to prevent an autopsy on his body, arguing that it would violate Islamic principles. The state eventually agreed to forego the autopsy, provided Gavin arranged for a mortuary to pick up his body by 7:30 p.m. after the execution. Supporters raised $4,000 to cover the transport of his body to Chicago for an Islamic burial.

In the days before his execution, Gavin had also requested specific final meal options, garments, and the inclusion of his imam, Aswan Abdul-Adarr, in the execution chamber. Gavin had planned to wear his kufi and have Abdul-Adarr pray with him during the execution. He claimed that Raybon had initially approved this arrangement according to state execution protocols.

It is not uncommon for death row prisoners to make final requests that push the boundaries of what is usually permitted. For example, last year, James Barber was allowed to lead a march to “When the Saints Go Marching In” before his execution in Alabama. His family was also permitted to bring a guitar to play “Amazing Grace” at the request of a correctional officer.

However, the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) has been less accommodating of requests from Muslim prisoners. Despite a small Muslim population in the state—less than one percent—the percentage of Sunni Muslims on death row is notably higher, around 12 percent. In 2019, when Domineque Ray requested that his imam be allowed to pray with him in the execution chamber, ADOC denied the request, citing security concerns. This decision was heavily criticized, including by a federal appeals court and three U.S. Supreme Court justices, with Justice Elena Kagan describing it as “profoundly wrong.”

For Keith Gavin, the situation was similarly problematic. Warden Terry Raybon initially told Gavin he could choose his final meal within a $25 limit. Gavin requested halal lamb, adhering to Islamic dietary laws that require meat to be slaughtered in a specific way. However, he had been unable to obtain halal food on death row. Gavin had previously tried to persuade ADOC to offer halal options, but his efforts were unsuccessful, partly due to Raybon’s unfamiliarity with halal food. (ADOC did not respond to inquiries about Raybon’s statement.)

Gavin explained that eating halal food was important to him as a Muslim, and he expressed that having a halal meal before his execution would be a “blessing.” The problem arose when Raybon stated that any outside meal must come from one of the few restaurants in the small town of Atmore, none of which serve halal food or lamb. Gavin’s lawyer, Kelly Huggins, attempted to arrange for Abdul-Adarr to pick up halal lamb from Mobile, about 50 miles away, but ADOC lawyers rejected this proposal.

In an email, ADOC lawyer Thomas McCarthy informed Huggins that Gavin could choose from the available options or the facility menu, and that visitors could provide snacks from the vending machines. When Huggins inquired about the possibility of a halal option, there was no response.

The prison chaplain also asked Raybon if he could drive to Mobile to retrieve the lamb, but Raybon rejected this suggestion as well. Dressed in a University of Alabama polo and gold warden badge, Raybon dismissed Huggins’ pleas, stating that a halal meal violated protocol without providing further explanation. Although ADOC’s execution protocol prohibits bringing in food, it does not specify that final meals must come from Atmore. I sent questions to ADOC about this policy but did not receive a response.

Ultimately, Gavin’s final meal consisted of junk food: a pint of butter pecan ice cream from his commissary account and snacks from the visitation room vending machine—Mountain Dew and peanut M&M’s.

Gavin’s disappointment was evident but not unexpected. The handling of his simple request for a halal meal raised further concerns about whether other aspects of his final wishes would be honored, such as wearing his kufi in the execution chamber or praying with his imam. Gavin was sentenced to death in 1999 by a 10-2 jury vote for the 1998 murder of William Clayton Jr. He maintained his innocence, claiming his cousin was responsible.

On appeal, Gavin’s lawyers challenged the fairness of his sentence, including the fact that Alabama and Florida are the only states allowing non-unanimous jury decisions for death sentences. Approximately 60% of death row inmates in Alabama were sentenced by split juries, according to a 2023 NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund report. Efforts to reform this practice have been unsuccessful, including a 2023 bill that did not advance out of committee.

Gavin’s attorneys have argued that his court-appointed trial lawyers failed to meet constitutional standards. They discovered that one of his attorneys was “heavily sedated” due to a broken foot as the trial approached. They also contended that his legal team presented a weak case during the sentencing phase, calling only two witnesses: his mother, who was inadequately prepared, and a minister who had counseled Gavin in prison.

Gavin’s appellate lawyers later uncovered details that they believe could have made a difference in his case. They found that Gavin grew up in poverty and violence in Chicago housing projects. He took on the role of caregiver for his 11 siblings and committed crimes to support his family. Gavin experienced severe abuse from his father and was attacked by a gang at 17, leading to a hospital stay. At 21, he killed the gang leader responsible for the attack and subsequently spent 17 years in an Illinois prison, where he was also attacked by gang members.

In 2020, a federal district court ruled that Gavin’s trial representation was so deficient that it violated his right to competent counsel. However, this decision was later overturned by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Following the setting of Gavin’s execution date in April, his legal team filed motions to halt the execution. When these motions were denied, Gavin chose to represent himself, filing his own last-ditch efforts to avoid execution.

On the afternoon of July 24, 2024, around 3 p.m., Gavin received a petition from Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall requesting that the U.S. Supreme Court allow the execution to proceed. With just an hour and a half before his scheduled execution, Gavin was left with no time to respond. He maintained a stoic demeanor, telling his supporters, “Don’t despair.”

As the execution time approached, Gavin’s legal team, now consisting of three members, discussed with him the details of the execution process, including how the IV lines would be set up. Gavin, who had a longstanding fear of needles stemming from his childhood, visibly recoiled at the discussion.

To shift his focus, Gavin began writing a final letter to his sister, Adriane, and placed it in a folder intended for her.

At 4:30 p.m., corrections officers, now in formal uniforms, arrived to escort Gavin. He was soon seen strapped to a gurney in the execution chamber, covered with a white blanket, with IV lines inserted in his arms. His index fingers were raised in an Islamic gesture of faith. His eyes were fixed on his imam, Aswan Abdul-Adarr, who stood beside him. Gavin was no longer wearing his kufi.

Warden Raybon, now in a suit, read the execution warrant and allowed Gavin to make his final statement. Gavin expressed his love for his family and recited, “La Ilaha Illallah Muhammadur Rasulullah,” meaning “there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is the messenger of God.”

Abdul-Adarr stepped forward to pray with Gavin, but the execution process began before the prayer could be completed. Gavin’s movement slowed, and his head eventually fell back as the sedative took effect. The execution was carried out, and Gavin was pronounced dead at 6:32 p.m.

Following the execution, ADOC issued a press release stating that Gavin had refused a final meal and made no special requests.

Later, Abdul-Adarr reported that the ADOC did not adhere to previously agreed-upon arrangements for Gavin’s final moments. Raybon had initially guaranteed that Gavin could wear his kufi and have traditional prayers recited, but these agreements were not honored. Abdul-Adarr said that the execution team started administering the lethal drugs while he was still praying with Gavin, preventing him from completing the rituals as planned.

The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) did fulfill its agreement regarding Gavin’s post-execution care. They did not perform an autopsy and transferred his body to an Islamic mortuary as promised. At the mortuary, Abdul-Adarr conducted the traditional Islamic washing of the body, performed three times, and prepared it for transport to Chicago. Gavin was buried there on Tuesday.

Abdul-Adarr has expressed his intention to file a complaint with ADOC about the handling of Gavin’s final moments. He has been reflecting on whether he should have raised concerns about the deviations from the agreed-upon plan while in the execution chamber but felt that it might not have changed the outcome. “It was very disrespectful,” he said. “They did not provide his last meal, removed his kufi, and did not follow the procedures they had promised.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours